Entropic Instruction Following: Does Semantic Coherence Help LLMs Follow Instructions?

Testing whether semantic relatedness of instructions affects a model's ability to follow them under cognitive load

I recently came across an intresting linkedin post discussing how the order of instructions impacts LLM performance.

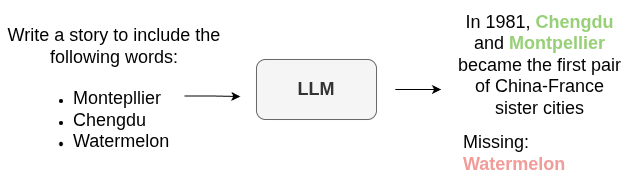

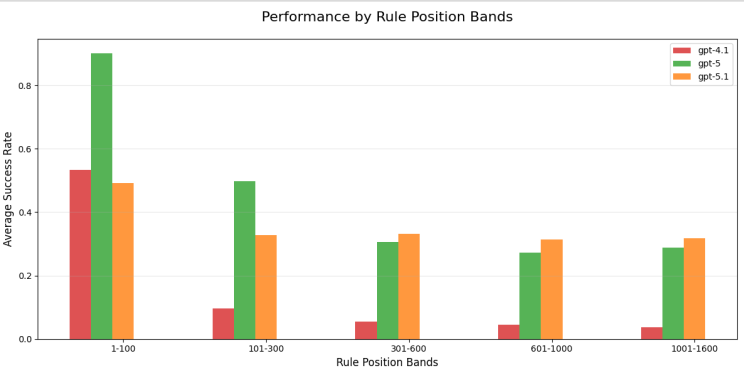

Alan Roth’s (the author of the linkedin post, who’s an HP at Alexa, Japan) experimental setup was designed to push the context window to its breaking point. His task was straightforward but demanding: Vocabulary Constraint. He fed models like GPT-5 and GPT-5.1 massive checklists containing up to 1,600 specific words and asked them to write a story that included every single one. By tracking adherence rule-by-rule, he generated a granular “performance heatmap,” revealing that while newer models are getting better at global optimization, they still exhibit distinct behavioral signatures, often favoring early instructions (primacy bias) or struggling to maintain focus in the middle of a long context.

An illustration of the rule following task

An illustration of the rule following task

His findings were compelling, but they sparked a question I couldn’t shake.

In his experiments, the rules were largely independent variables, isolated tasks meant to check capacity. But in the real world (and in the training data), language is rarely a bag of independent constraints. It’s structured. It flows.

My hypothesis was simple: Does the semantic relatedness of instructions affect a model’s ability to follow them?

If I ask a model to include the words “School,” “Teacher,” and “Blackboard,” the semantic proximity (low perplexity) should theoretically make the generation task easier than if I ask for “Azimuth,” “Potato,” and “Carburetor.”

To test this, I built a new experimental framework called Entropic Instruction Following to stress-test models against the chaos of their own inputs.

The Experimental Design: Stress-Testing the Context Window

To rigorously test whether semantic coherence impacts instruction following, we need a dataset that isolates “entropy” as a variable. If we just ask a model to write a story about “food,” it might succeed simply because it has seen a million recipes, not because it is handling the context well. To avoid this, I iterated on the design to remove these biases.

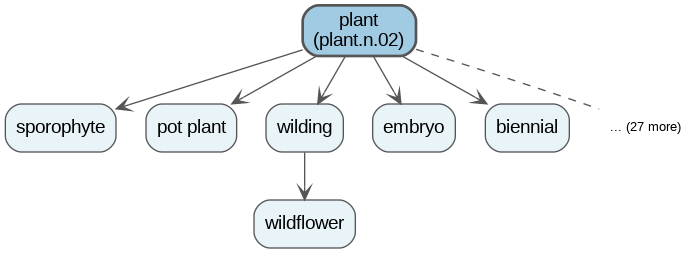

1. Defining “Coherence”: the WordNet seed

When I say “Coherent,” I don’t just mean words that vaguely sound alike. I mean words that share a structural relationship in a lexical database.

Using NLTK and WordNet, I wrote a word data generator that anchors to a specific synset seed. For example, if the seed is plant.n.02, the generator traverses the hyponym tree (the “is-a” relationships) to find all specific descendants of that concept.

Example of words generated by using plant as a seed (plant as seed haha :p)

Example of words generated by using plant as a seed (plant as seed haha :p)

It might pull tiger, iguana, eagle, spaniel, and plankton. These words are distinct entities, but they share a high degree of mutual information. Contrast this with the “Random” lists, which are sampled uniformly from the entire dictionary, ensuring maximum semantic distance between tokens.

2. Extending the concepts space

In my earliest iterations, I relied on a single semantic domain (specifically food.n.02). While this was great for debugging, it posed a scientific risk: What if a specific model just happens to be really good at cooking stories?

To prove that Coherence Bias is a fundamental property of LLMs (and not just a quirk of how they like to talk about omelets :p) I expanded the scope significantly. I moved from a single seed to 10 distinct WordNet synset seeds covering a wide spectrum of human concepts:

Concrete: food.n.02, artifact.n.01, animal.n.01, plant.n.02, substance.n.01

Abstract/Social: cognition.n.01, communication.n.02, event.n.01, location.n.01, person.n.01

3. Reducing within seed noise

To ensure we are measuring signal and not noise, we implement a two-layer randomization strategy:

10 Semantic Domains: As mentioned above, we test across 10 different topics.

10 Random Variations: For every single configuration (e.g., “Animals”, “200 rules”, “Coherent Pattern”), I generate 10 unique variations via random sampling.

This distinction is crucial. It means we aren’t just testing “Animals” once. We are generating 10 different lists of animals by shuffling the word pool and sampling without replacement. This ensures that if a model fails, it’s failing because of the entropy profile of the task, not because it got “unlucky” with a specific difficult word list.

4. Atomic constraints: single words only

Finally, I added a strict constraint on the word generator: all words in the dataset are filtered to be single, alphanumeric words. I explicitly filter out multi-word expressions (like “ice cream”) or hyphenated terms.

Complex or hyphenated words might introduce confusion for the model. By restricting the task to atomic units of meaning, we ensure the model’s struggle is purely about semantic organization, not lexical formatting.

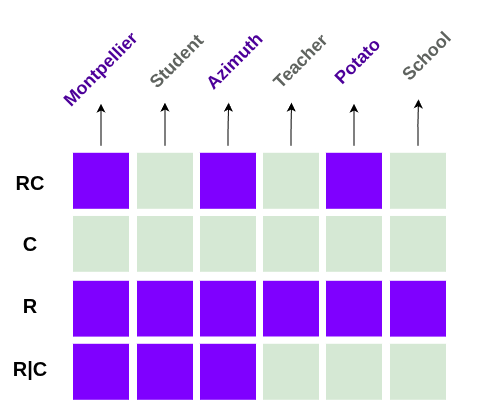

5. Disentangling position from entropy

This is the core of the experiment. We know LLMs suffer from “Lost in the Middle” or positional biases (primacy/recency). If a model fails to follow a rule at index #350 of 400, is it because the context is too long, or because the rule is random?

To answer this, I chose 7 specific patterns designed to dissociate positional bias from coherence bias:

The Baselines: c (Pure Coherent) vs r (Pure Random).

The Blocked Mixes: c|r vs r|c.

The “Bookends”: c|r|c vs r|c|r. These test if the model can “recover” attention after a chaotic middle section.

The Stress Test: cr (Alternating). This switches context every single word (Coherent → Random → Coherent…), creating maximum high-frequency semantic noise.

An example of alternating coherence and randomness (the top row)

An example of alternating coherence and randomness (the top row)

6. Model selection

For this experiment, I focused on models under 8B parameters, roughly the threshold for what consumers can run on their laptops (without quantization). I selected a mix of old and new architectures (Mistral.7B.V0, Llama-3.2-1B, Olmo-3-7B, Falcon-H1-7B) to capture architectural diversity rather than focusing on any single model family.

I also included a smaller model (Llama-3.2-1B) to explore whether distinct behaviors emerge at lower parameter counts. While this added an interesting data point, I chose not to expand this into a full model-size analysis, as it would have introduced another dimension requiring significant additional compute and analysis time beyond my current resources.

7. Scale and input length

We are testing rule counts of 50, 200, and 400 words. I capped the upper bound at 400 for two practical reasons.

First, looking at Roth’s results, even state-of-the-art models exhibit substantial failure rates at this volume. We don’t need 1,600 rules to see the cracks start to form.

Performance of recent ChatGPT models on rule following, split by rule position bands (bins). Image credit: Alan Roth

Performance of recent ChatGPT models on rule following, split by rule position bands (bins). Image credit: Alan Roth

Second, I don’t have a GPU cluster at my disposal :’). Constraining the total length allowed me to allocate my compute budget to what I considered more critical dimensions: specifically the width and depth of the entropy investigation (10 seeds, 7 patterns, and 10 variations) rather than just raw token count.

It is important to note that this is not a context-window overflow test. Even at 400 rules, the input length remains well within the comfort zone of modern models:

Input ≈ 1.4 (tokens per word) × 400 (Max number of rules) + 100 (Sys+Usr Prompts tokens) = 700 tokens.

Since we are using models with context windows well above that threshold of tokens (like Mistral, Llama 3, and Olmo), any failure to follow instructions is a failure of attention and reasoning, not memory capacity.

The Results: Coherence Matters But Not Uniformly

The short answer? Yes, semantic coherence dramatically improves instruction following but only under specific conditions. In the long answer regime, we see something nuanced about how LLMs process constraints under cognitive load.

1. Models degrade dramatically with rule scale

First, let’s establish the baseline: All models struggle as rule counts increase, but they don’t all struggle equally.

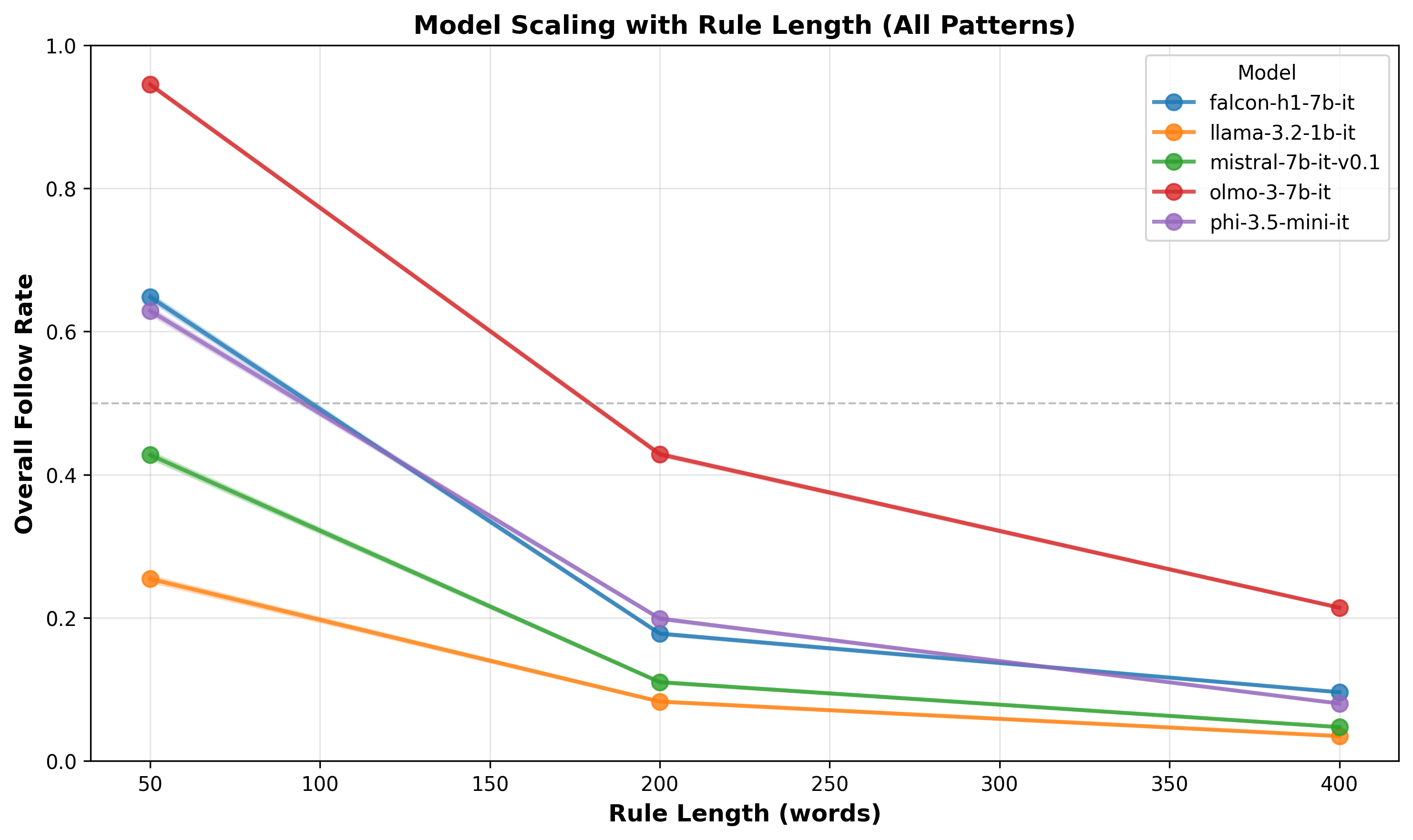

Overall results of models on rule following (collapsed under the seed, pattern, and variations axes)

Overall results of models on rule following (collapsed under the seed, pattern, and variations axes)

At 50 rules, even the smallest model (Llama-3.2-1B) has some level of compliance (~25%) but at 400 rules it collapses to ~5%. Ai2’s Olmo-3-7B (7B parameters) achieves ~95% at 50 rules but crashes to ~24% at 400. Although Mistral.7B.V0 starts at ~43%, and Falcon-H1-7B at ~0.65, both drop to ~0.1 at 400 rules.

Looking at how 3 models of the same size exhibit largely different results, especially at small rule counts, indicates that model size might not be a good predictor for this task, at least when comparing in the similar parameter size buckets.

2. The coherence advantage

Now for the central question: Does coherence actually help?

The answer depends entirely on how hard you’re pushing the model.

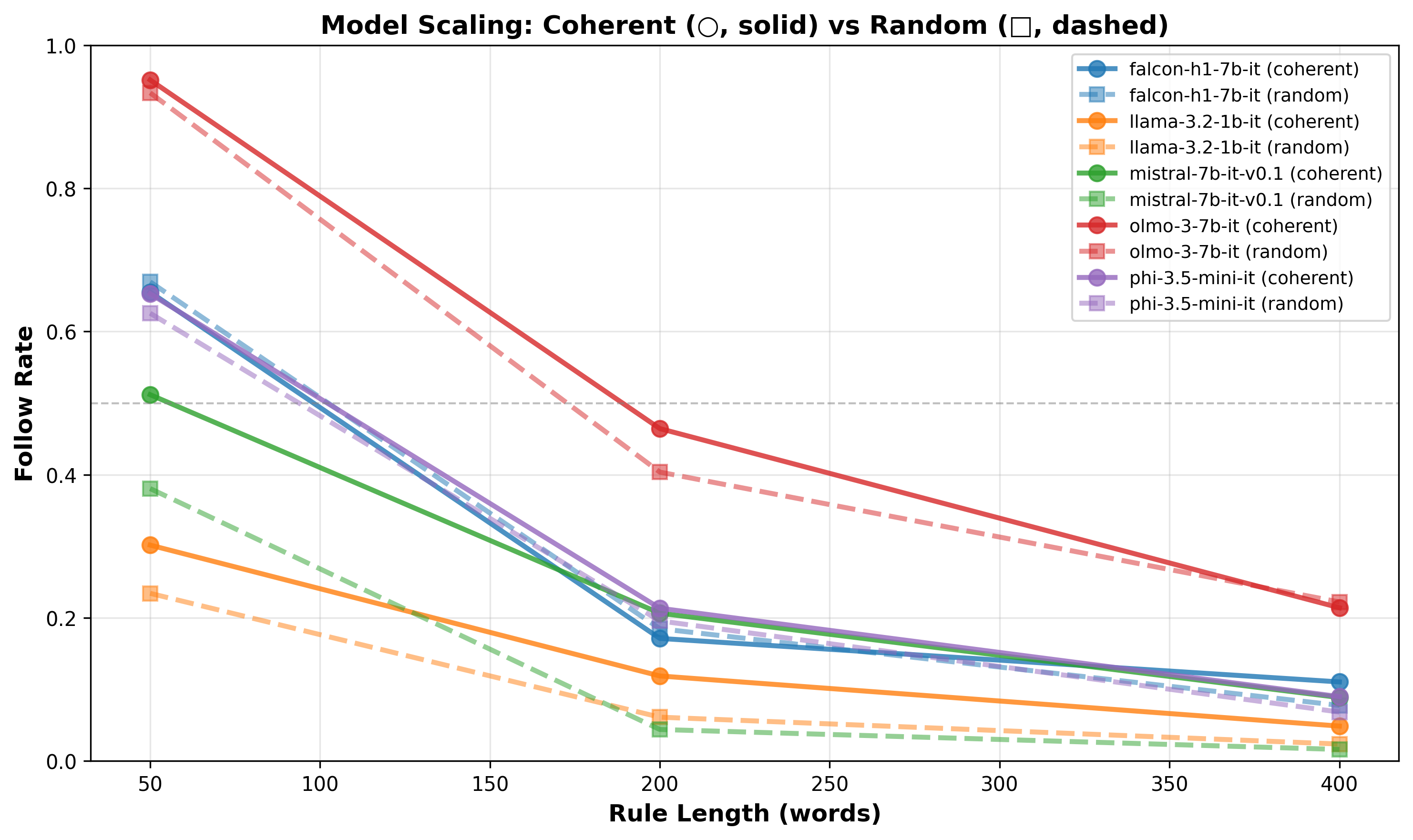

Results across rule sizes, for pure random vs pure coherence (collapsed under seed and variations)

Results across rule sizes, for pure random vs pure coherence (collapsed under seed and variations)

2.1. The smooth landscape: 50 rules

When the task is short (50 rules), the models are powerful enough to not be affected by the randomness (p > 0.05), except for Mistral AI’s model on pure coherence (we’ll get back to this one later).

We’ve seen before that we can see drastically different performances at the same model size, but it remains to investigate if differently sized models react in more drastic ways. (looking at you llama model :O)

Model performance on 50 rules across different patterns collapsed under seed and variations

Model performance on 50 rules across different patterns collapsed under seed and variations

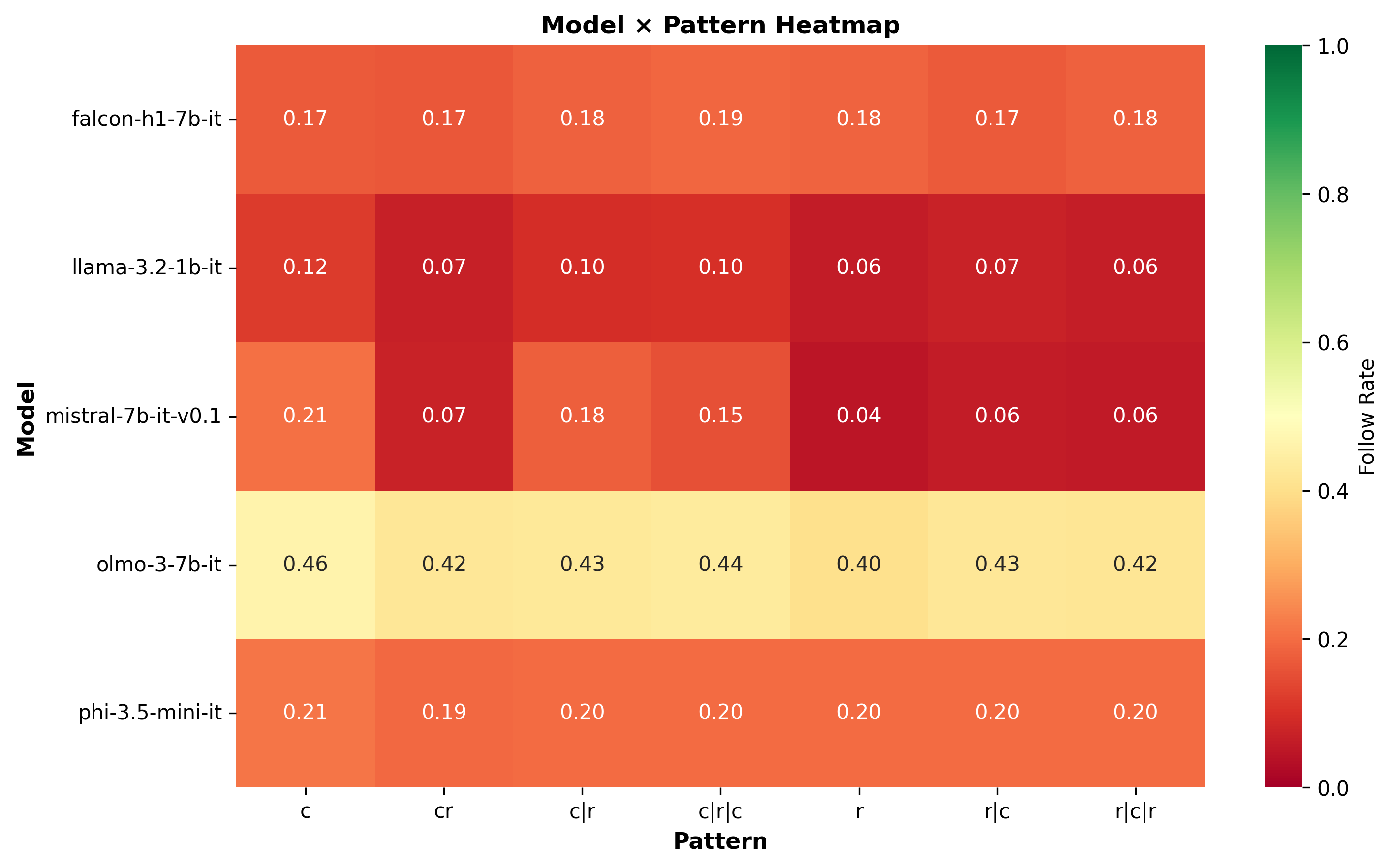

2.2. The beginning of the end: 200 rules

At 200 rules, the gap widens. Some models experience drastic relative score drops, especially Mistral.7B.V0, while others remain impressively unphased.

Model performance on 200 rules across different patterns (collapsed under the seed and variations axes)

Model performance on 200 rules across different patterns (collapsed under the seed and variations axes)

2.2.1 The Mistral case

This is perhaps a good moment to unfold the axis of seed and variations to see what’s going on with individual models, starting with Mistral.7B.V0:

The first question we ask here is whether specific seeds affect this model differently:

Mistral.7B.V0 results across different seeds, patterns and variations

Mistral.7B.V0 results across different seeds, patterns and variations

Looking at the plot we can see a few things:

- In some combinations of (seed, pattern) has an effect on the model like (plant, c (coherent)) or (animal, random). My unsurprising guess is that this is training data diversity induced, but will likely need more investigation.

- On the other hand we see seeds seems to create an indifference to patterns, usually with more abstract concepts like: artifact or substance.

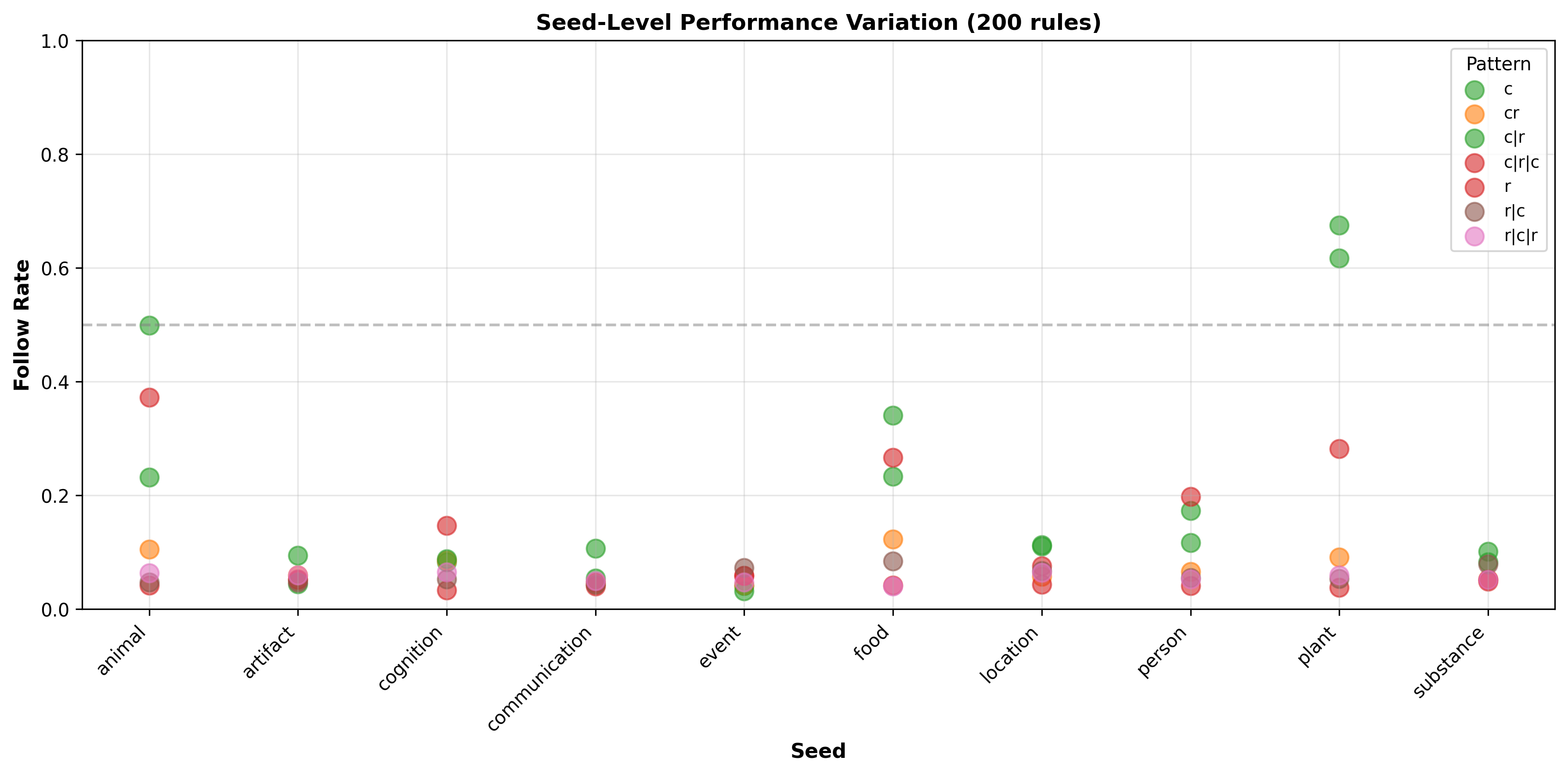

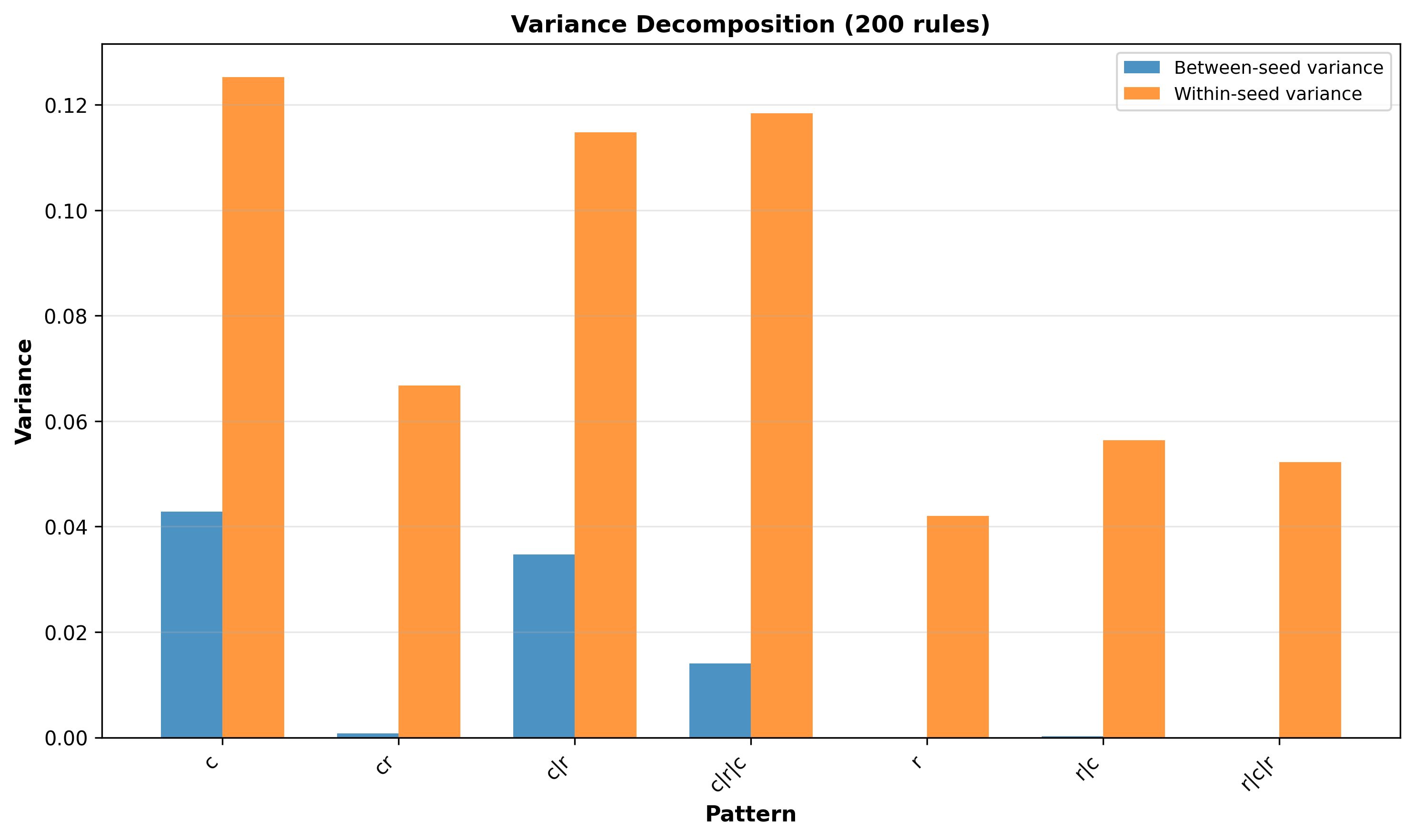

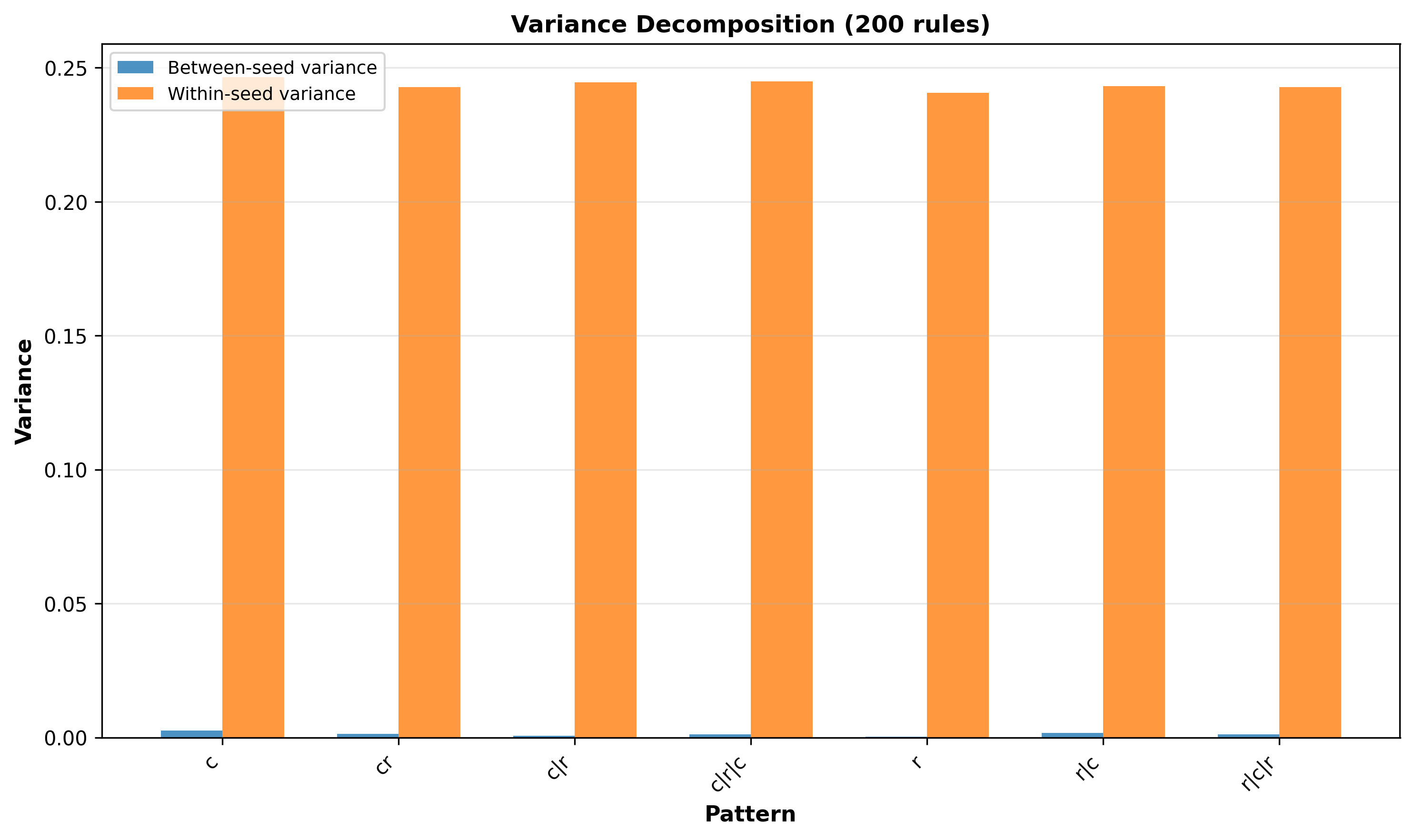

Our next question is whether there’s any actual consistency in patterns across the different seeds, and to do that we compute the within-seed variance and between-seed variance, and get the following plot:

Within-seed and between-seed variance for Mistral.7B.V0

Within-seed and between-seed variance for Mistral.7B.V0

We note the following:

- The within-seed variance is much more present than between-seed variance. This holds across all patterns.

- In some patterns we see close to no between-seed variance. Interestingly this happens when it’s random, alternating randomness (cr), OR when we start with randomness, raising the question if this has to do with the sneaky positional bias.

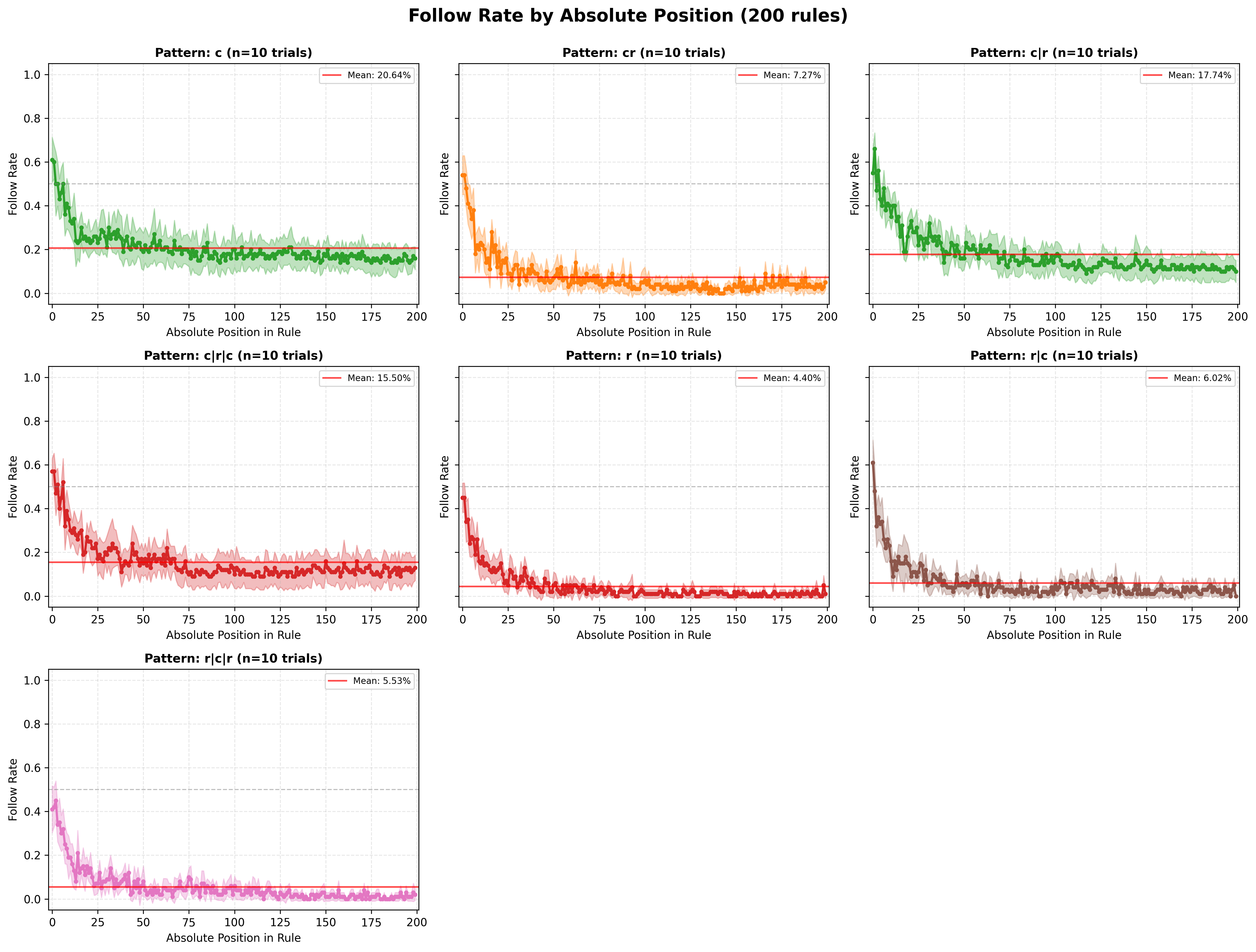

Now that we have explored a bit the internals, let’s inspect the effect of positions and patterns while collapsing the other dimensions by looking at the results across 10 trials (and 10 seeds):

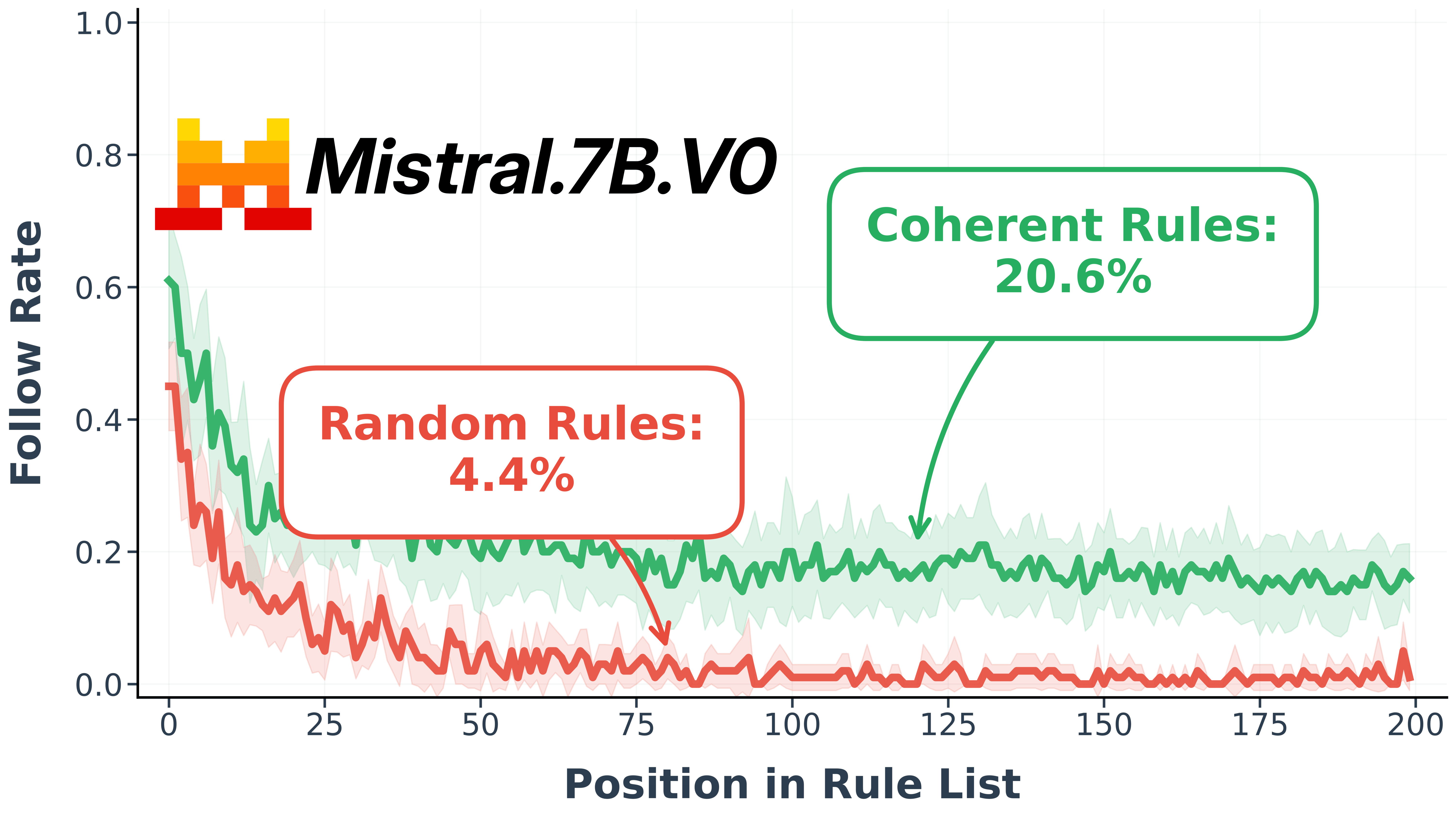

Results of the Mistral model in different patterns, across index positions in the 200 rules regime

Results of the Mistral model in different patterns, across index positions in the 200 rules regime

For this particular model we can see that the pattern type behaves like a bias, i.e., it lifts the curve up, while clearly keeping the positional bias (tending to attend to the first tokens of a sequence). This can clearly be seen when comparing the total random and totally coherent, where the means go from 4.4% to 20.64%.

2.2.2 The Olmo case

Looking at the previous heatmaps we saw that the Olmo model had not been affected much by the pattern overall, but this stability actually persists even at the seed level, where the scores seem to cluster much more.

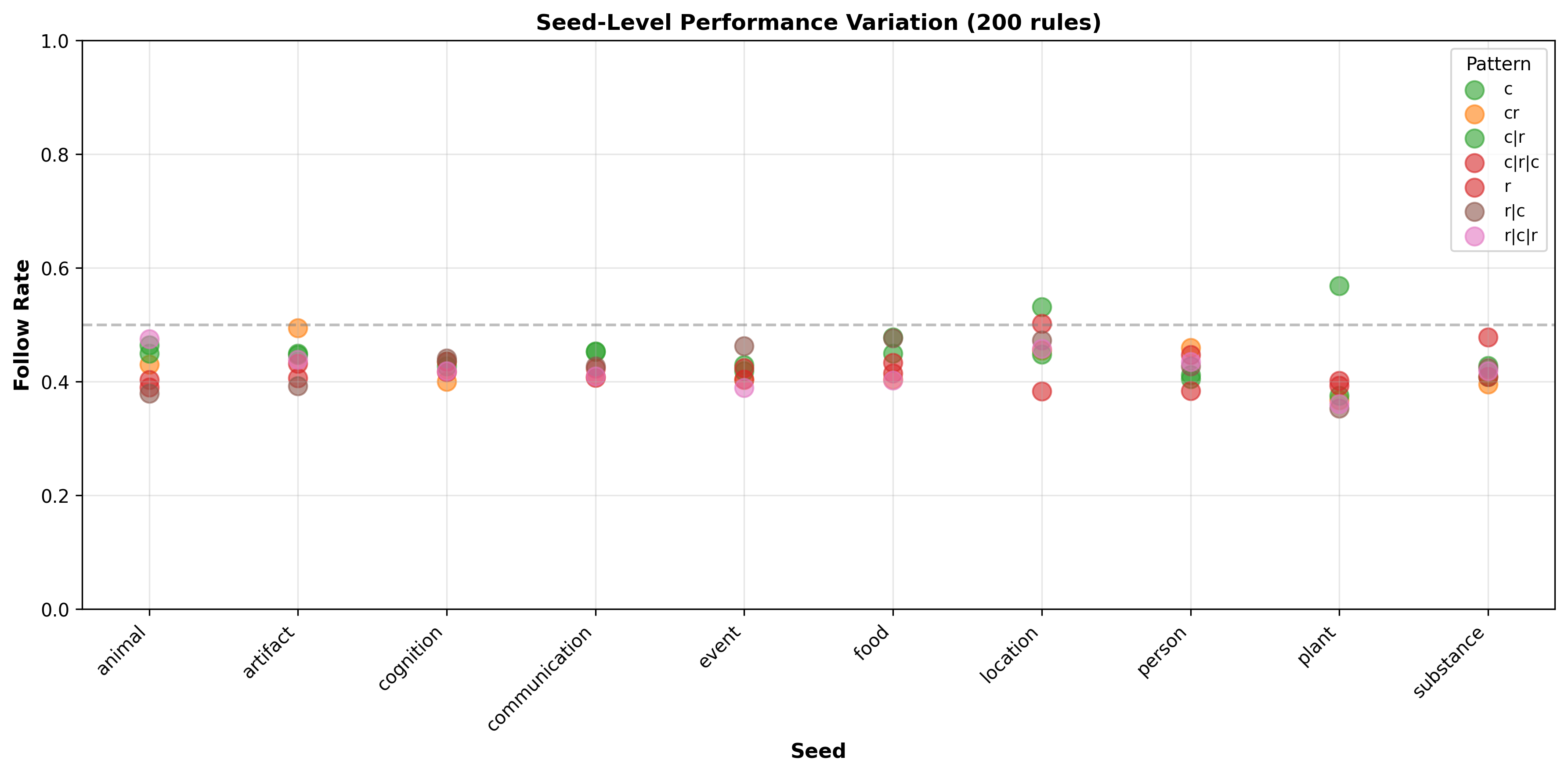

Olmo-3-7B’s results across different seeds, patterns and variations

Olmo-3-7B’s results across different seeds, patterns and variations

Another important deviation of this model from the behavior of the Mistral model is with regards to both:

- The between-seed variance, which can be observed in the first but not in the Olmo model.

- The within-seed variance is much more present (2x the max) and consistently across patterns when compared to the Mistral model.

Olmo-3-7B’s between-seed and within-seed variance results

Olmo-3-7B’s between-seed and within-seed variance results

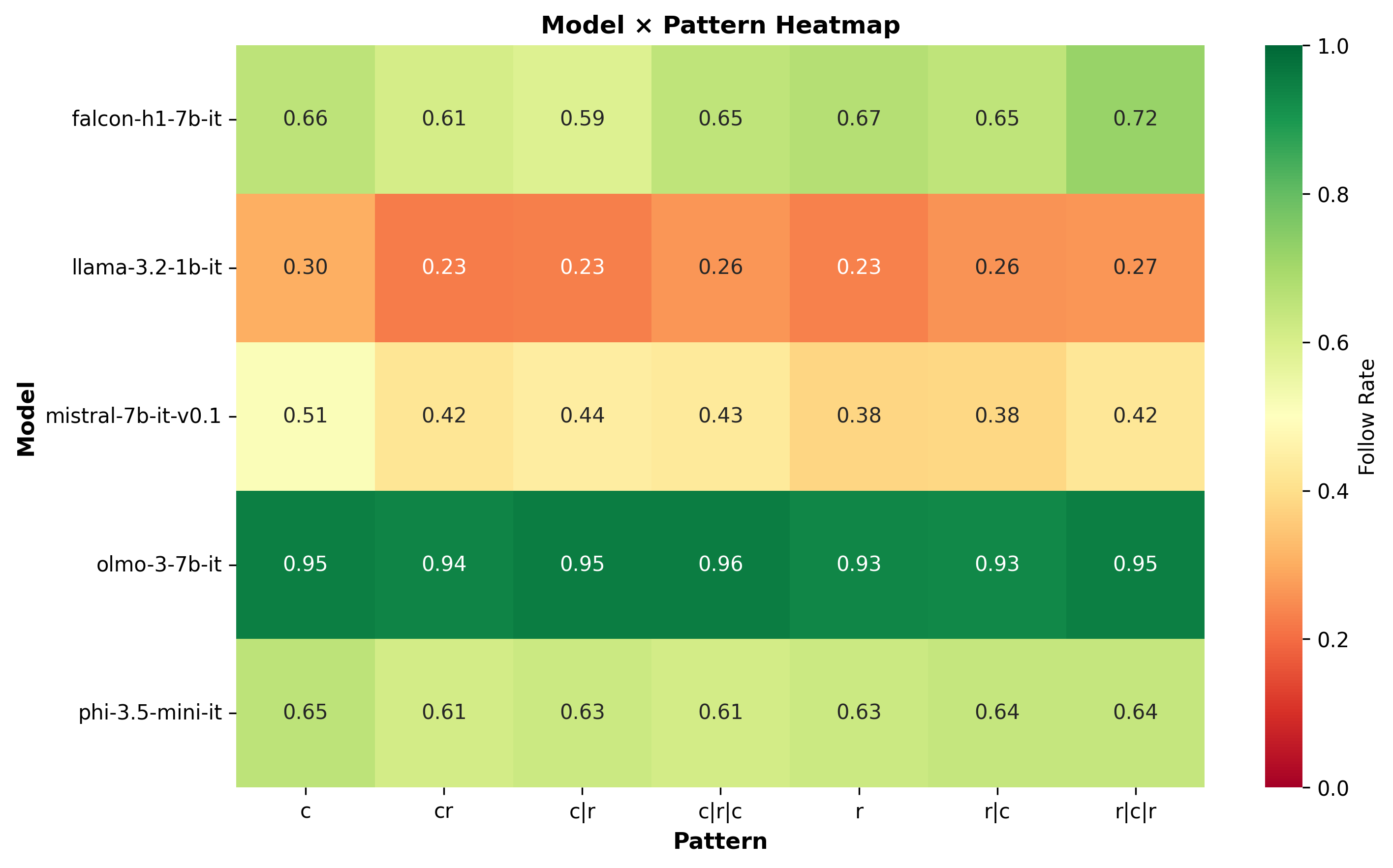

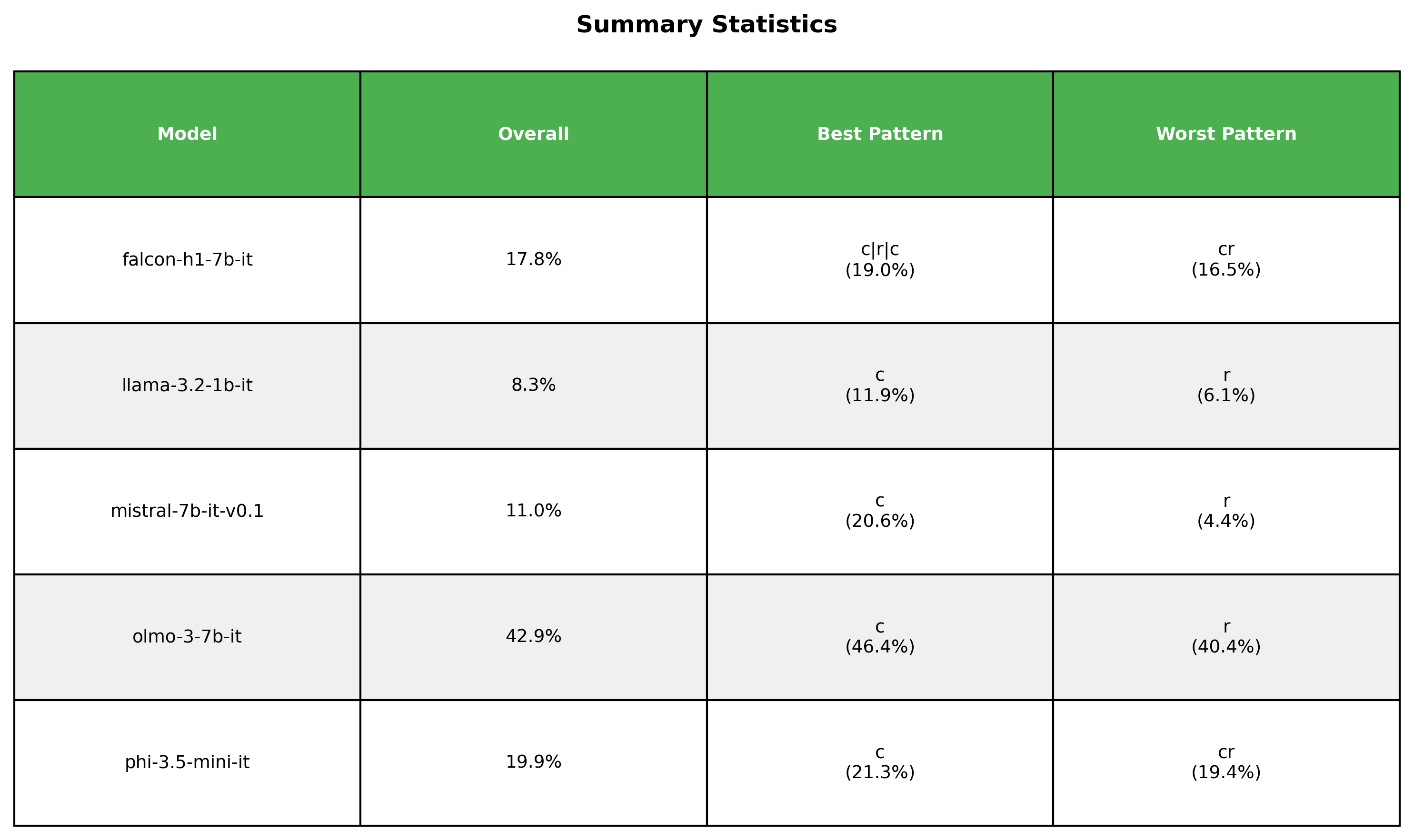

2.2.3 The best and worst at 200 rules

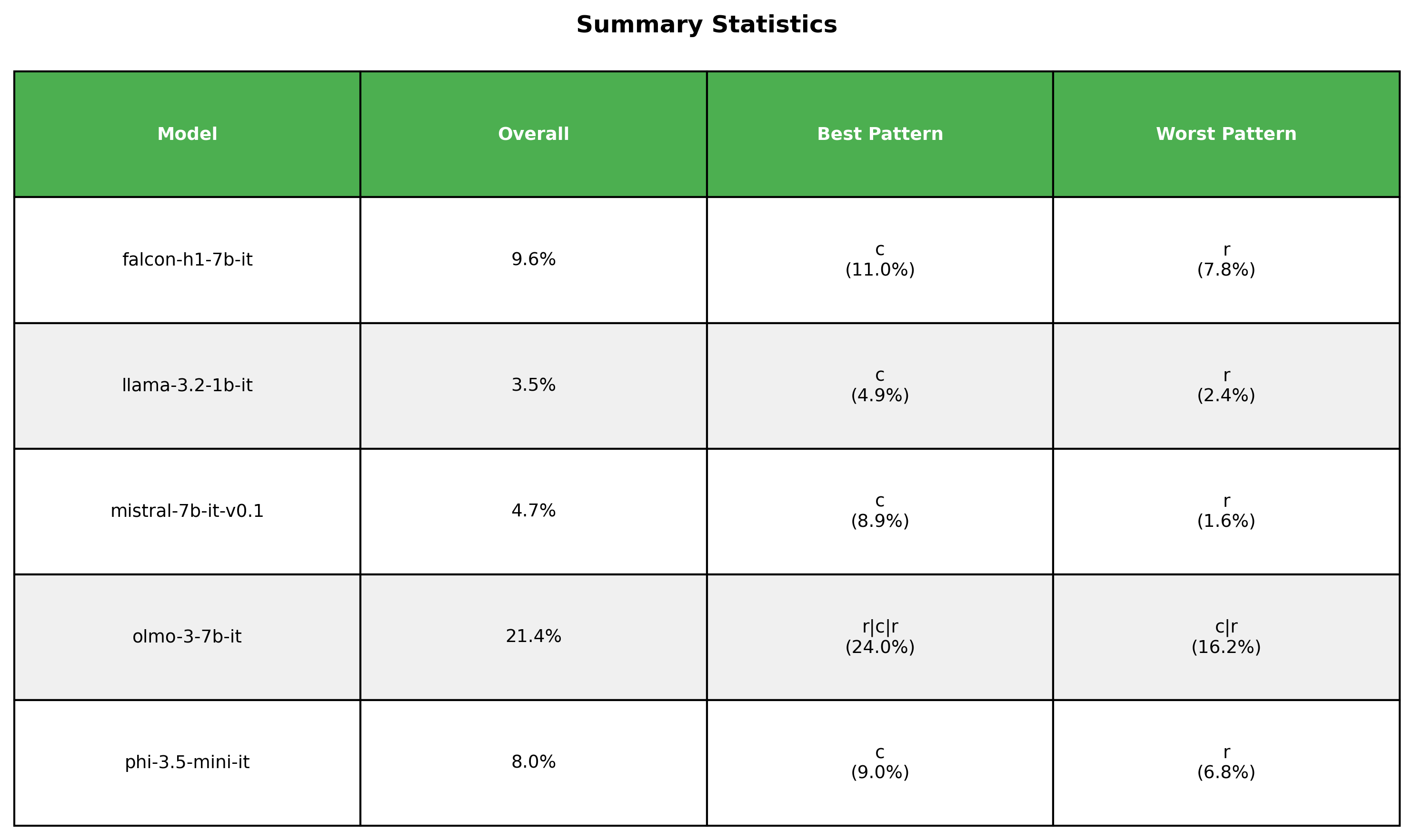

Let’s go back and take a look at the broader image. The following table describes the best and worst patterns for each model at the 200 rules regime.

Most and least favorable patterns for each model in 200 rules regime

Most and least favorable patterns for each model in 200 rules regime

For all the models the best scores come from either full coherence or sandwiching the randomness between coherence.

Regarding the worst results, they all come from pure randomness or alternating randomness and coherence, what I essentially described as high entropy.

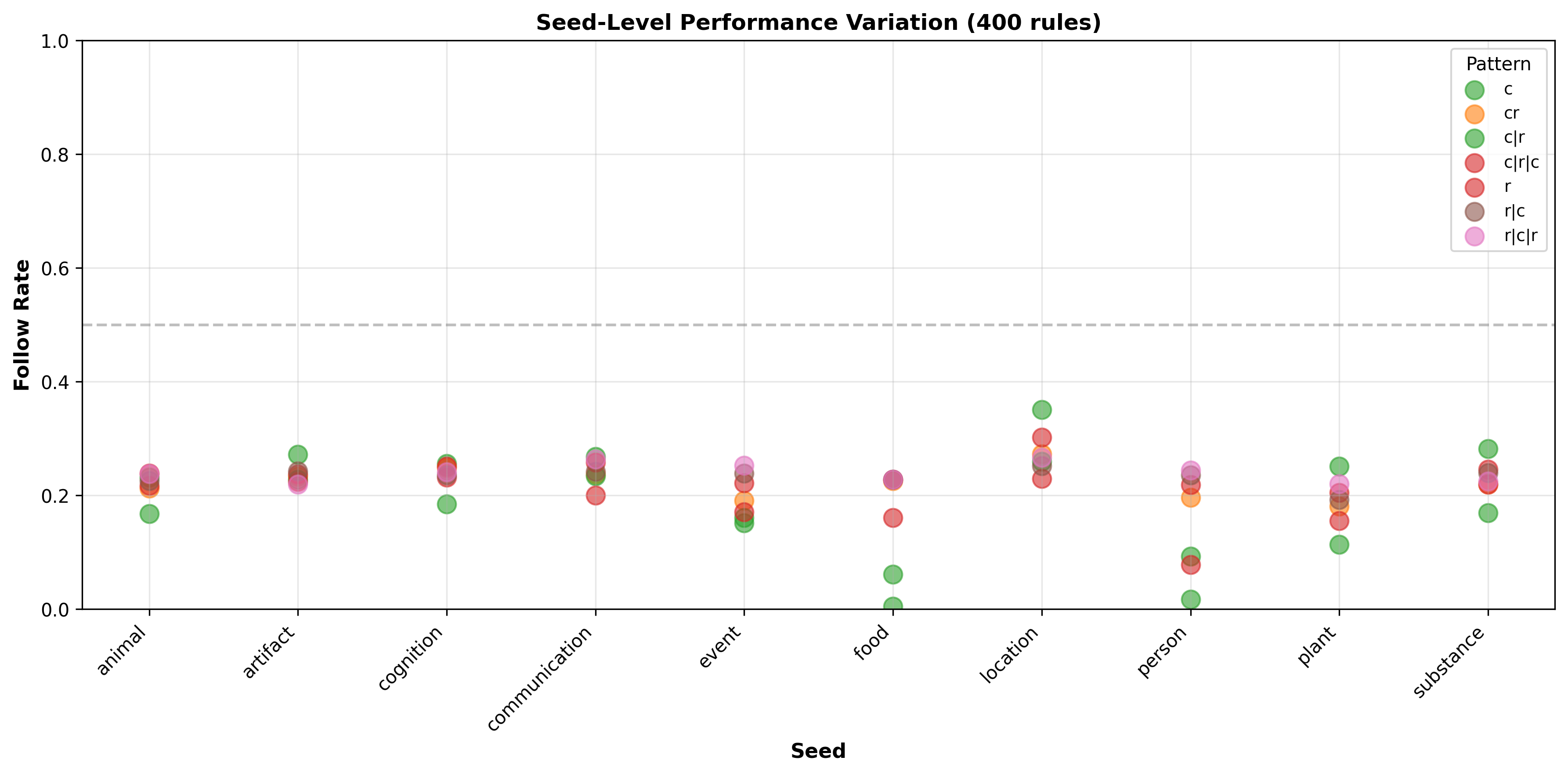

3. Confusion rules at 400 rules

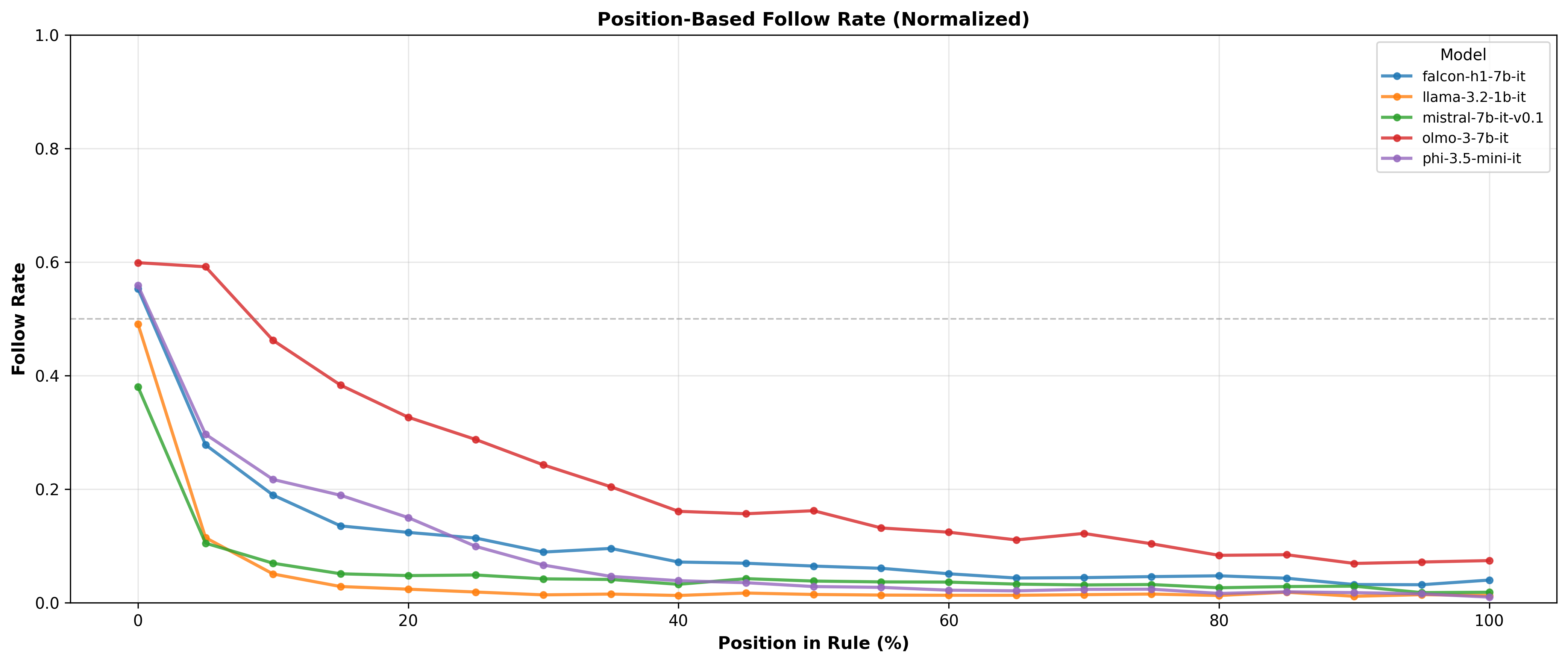

The graph below compares the follow rate of different models across position:

Performance of different models across the positions in the 400 rules regime

Performance of different models across the positions in the 400 rules regime

An important element to note is that models do not maintain their spot in the leaderboard across different positions, which can make model selection even trickier.

Going back to the inclinations to specific patterns, we see that the tendency to prefer coherence over randomness still holds across all models, except… again for the Olmo model.

Most and least favorable patterns for each model in the 400 rules regime

Most and least favorable patterns for each model in the 400 rules regime

Tracing back the failures of Olmo back to the seeds level, we can see that it dramatically fails for the food and person categories, which is very curious given that we didn’t see this behavior in the 200 rules regime for the same model.

Olmo-3-7B’s results across different seeds, patterns and variations at 400 rules

Olmo-3-7B’s results across different seeds, patterns and variations at 400 rules

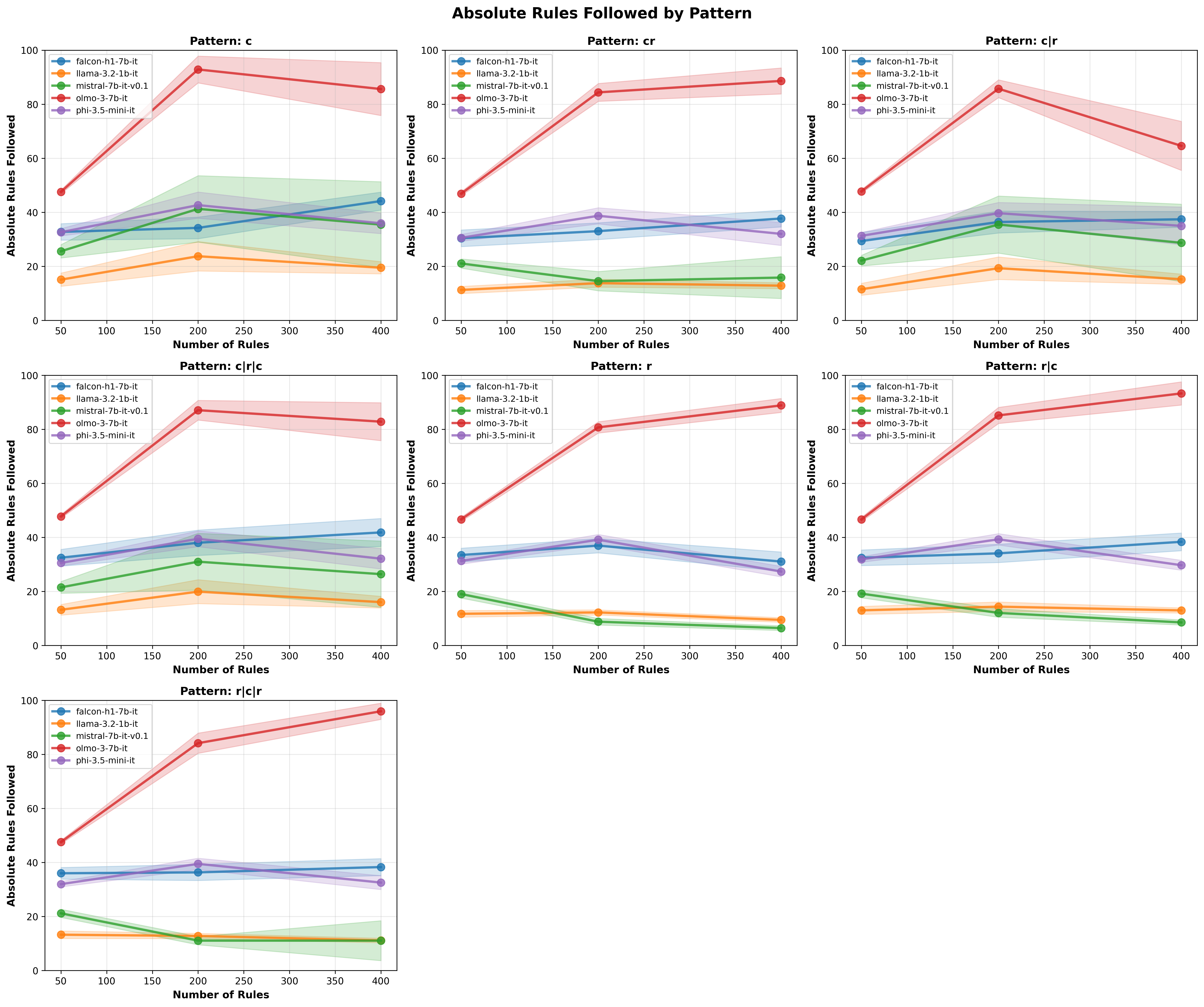

4. Let’s talk absolutes

We have not yet addressed a critical element. Up until now our focus was only on relative results, but what about what actually matters: the absolute scores? To investigate that we plot the raw number of rules followed for different patterns and different rules.

Absolute number of rules followed across different rule counts, patterns and models

Absolute number of rules followed across different rule counts, patterns and models

These are perhaps some of the most important findings:

- Going from 50 rules/constraints to 200 (4x) can be beneficial for some models like Olmo-3, but isn’t a global truth.

- Doubling from 200 rules to 400 can in some cases hurt the performance or at the most provide marginal benefits when taking into account the additional compute and memory cost (I had to say this at some point lol: quadratic for attention).

Brief Conclusion

I’d rather not draw hasty conclusions. I’d maybe suggest that if you are designing prompts with massive constraint lists (e.g., complex coding guidelines or legal requirements), you might want to add “coherence clustering” to your prompt engineering experiments, sorting the clusters by importance, and front loading them by that order.

Future Directions

While I find the results to be interesting, many questions remain to be answered:

- Do these patterns hold for other types of constraints? If I ask for specific code requirements, formatting rules, or stylistic constraints, does semantic coherence still predict adherence?

- What are the underlying mechanisms driving these differences? Is it purely attention-head allocation, or something deeper in how concepts are represented in the residual stream?

- This fundamentally asks a question about generalization: if we train on a diverse set of topics, is the model able to “grab” the individualities from that learned diversity to form a story about a specific topic? Or does it just memorize specific low-entropy templates?

Code & Data

The complete code for reproducing these experiments, including the word generators, evaluation scripts, and raw results, is available on GitHub.

Final words

Before closing I wanted to thank Lightning AI for providing monthly free credits to students/researchers ((づ˶˃⤙˂˶)づ H100s)… The time between experimentation cycles would have made this a stinky experience.

A moderately funny meme designed at 12AM, likely not funny in the morning

A moderately funny meme designed at 12AM, likely not funny in the morning