Why Modern LLMs Dropped Mean Centering (And Got Away With It)

Visualizing the hidden 3D geometry behind Layer Normalization and uncovering the mathematical trick that makes RMSNorm tick.

While I was reading through some papers about the motivation behind Hyper-Connections, which linked to some artifacts about normalization, and their position (post/pre layerNorm), I stumbled upon some great notes by Andy Arditi on the geometry of Layer Normalization. His write-up highlighted a brilliant paper by Paul M. Riechers titled Geometry and Dynamics of LayerNorm.

The math in both pieces is incredibly elegant, but I wanted to give it a shot, in my style, and attempt to give this knowledge more visibility to the community.

When we talk about operations inside a Transformer, we usually look at raw algebra. But if we strip away the indices and summations, normalization is actually a beautiful sequence of spatial transformations: projections, spheres, and stretching hyper-ellipsoids.

My goal here is to make this visually intuitive, so you’ll be able to manipulate these concepts in your head. I’ve built a 3D toy simulation to show exactly what happens to our data during standard LayerNorm, including the sneaky effect of the $\epsilon$ parameter (yes again! funny enough, I wrote about $\epsilon$ trapping the Adam optimizer, and here it is causing trouble again :p).

But more importantly, I want to share a derivation I’ve made, which I’m not aware has been covered in any material, which shows exactly how the modern RMSNorm relates to standard LayerNorm, both mathematically and geometrically.

Let’s jump in.

1. The Anatomy of LayerNorm

Given an activation vector $\vec{x} \in \mathbb{R}^n$, the standard LayerNorm operation is defined as:

\[LayerNorm(\vec{x}) = \vec{g} \odot \frac{\vec{x} - \mu_{\vec{x}}}{\sqrt{\sigma_{\vec{x}}^2 + \epsilon}} + \vec{b}\]We can break this down into three distinct geometric phases.

Phase 1: Mean Centering (The Orthogonal Complement)

Let’s start with the intuition. What happens when you subtract the mean from a set of numbers? By definition, the sum of those new, centered elements becomes exactly zero.

Mathematically, summing the elements of a vector is equivalent to performing a dot product with a vector of all ones ($\vec{1}$). So, if the sum of our centered vector is zero, its dot product with $\vec{1}$ must also be zero.

Just a quick reminder: when the dot product of two non-zero vectors is zero, it means they are perfectly perpendicular (orthogonal) to each other.

This tells us that the mean-centered data is orthogonal to the vector of ones. So, while $\vec{x}^{(1)} = \vec{x} - \mu_{\vec{x}}$ looks like a simple statistical shift, geometrically, it’s a projection. By subtracting the mean, we are taking our data vector and stripping away its “shadow” along the diagonal axis of the space (see Appendix 1 for the mathematical derivation).

\[\vec{x}^{(1)} = \vec{x} - (\vec{x} \cdot \hat{1})\hat{1}\]By definition, taking a vector and removing its projection along a line forces the result to live in the space perpendicular to that line. We are projecting our $n$-dimensional activations onto an $(n-1)$-dimensional flat plane (the orthogonal complement of $\vec{1}$).

Notice how the data (blue) is projected straight down onto the cyan plane (where $x+y+z=0$), resulting in the centered points (green).

Notice how the data (blue) is projected straight down onto the cyan plane (where $x+y+z=0$), resulting in the centered points (green).

Phase 2: Variance Normalization (The Hypersphere)

Now for the variance. Intuitively, dividing by the standard deviation forces all our data vectors to have a consistent spread.

It feels incredibly natural to assume that dividing by this deviation projects the vector onto a unit sphere (a sphere with a radius of 1). But this is a mathematical illusion!

To project a vector onto a unit sphere (radius 1), you must divide it by its exact geometric length (the L2 norm, $\lVert\vec{x}\rVert$)

Standard deviation ($\sigma$) isn’t the geometric length! Because variance is the average of the squared distances ($\sigma^2 = \frac{1}{n}\lVert\vec{x}^{(1)}\rVert^2$), dividing by $\sigma$ actually projects our data onto a hypersphere of a much larger radius, specifically $\sqrt{n}$ (see Appendix 2 for derivation).

\[\vec{x}^{(2)} = \sqrt{n} \frac{\vec{x}^{(1)}}{||\vec{x}^{(1)}||}\] The mean-centered points (green) are radially pushed or pulled until they lock onto the intersection of the flat plane and a hypersphere of radius $\sqrt{n}$ (the red ring).

The mean-centered points (green) are radially pushed or pulled until they lock onto the intersection of the flat plane and a hypersphere of radius $\sqrt{n}$ (the red ring).

Phase 3: The Affine Transformation ($\gamma$ and $\beta$)

We just spent all that compute forcing our data onto a perfectly rigid, predictable spherical ring. Why? So the neural network can safely warp it into whatever shape it actually needs to learn!

The learned parameters $\vec{g}$ (often called $\gamma$) and $\vec{b}$ (often called $\beta$) apply an affine transformation:

\[\vec{x}^{(3)} = \vec{g} \odot \vec{x}^{(2)} + \vec{b}\]Because $\vec{g}$ is applied via element-wise multiplication ($\odot$), it stretches our perfect sphere unevenly along the different feature axes, transforming the hypersphere into a hyper-ellipsoid. Then, adding the bias $\vec{b}$ simply picks up that ellipsoid and translates it through space.

The $\gamma$ parameter stretches the perfect spherical ring into an elliptical shape, scaling different feature dimensions based on their learned importance.

The $\gamma$ parameter stretches the perfect spherical ring into an elliptical shape, scaling different feature dimensions based on their learned importance.

The $\beta$ *parameter simply translates the entire newly formed ellipsoid to a new center of gravity in the latent space.

The $\beta$ *parameter simply translates the entire newly formed ellipsoid to a new center of gravity in the latent space.

The $\epsilon$ Anomaly: A Solid Ball, Not a Hollow Shell

Let’s think about this intuitively: if you divide a number by something slightly larger than itself, the result is always less than 1.

In the denominator of LayerNorm, there is a tiny constant $\epsilon$ (usually $10^{-5}$) added for numerical stability to prevent division by zero.

By adding a positive $\epsilon$, the denominator ($\sqrt{\sigma_{\vec{x}}^2 + \epsilon}$) becomes strictly larger than the true standard deviation.

Because of this geometric trick, the denominator is always slightly larger than the true variance (see Appendix 3 for derivation):

\[||\vec{x}^{(2)}|| = \sqrt{n} \left( \frac{||\vec{x}^{(1)}||}{\sqrt{||\vec{x}^{(1)}||^2 + n\epsilon}} \right)\]This means the data never actually reaches the surface of the $\sqrt{n}$ sphere.

Furthermore, because LayerNorm calculates a different variance for every single token, $\epsilon$ pulls on them unevenly:

“Loud” Data (High Variance): The signal dwarfs $\epsilon$, so the fraction is basically 1. The point lands right on the inside surface of the sphere.

“Quiet” Data (Low Variance): The signal is tiny, so the $n\epsilon$ constant dominates the denominator. The point is violently pulled inward toward the origin.

Because of $\epsilon$, LayerNorm doesn’t project data onto a hollow, razor-thin shell. It projects data into a solid ball, with points distributed radially based on their original variance!

With $\epsilon$ applied, large variance points (blue) hit the target ring, while small variance points (red) fall short, getting trapped closer to the origin.

With $\epsilon$ applied, large variance points (blue) hit the target ring, while small variance points (red) fall short, getting trapped closer to the origin.

The Main Event: Unmasking RMSNorm

Modern LLMs have largely abandoned standard LayerNorm in favor of RMSNorm (Root Mean Square Normalization).

Let’s start with the intuition again. Why would we ever drop the mean centering? Deep neural networks tend to have activations with a mean that naturally hovers close to zero anyway. If the mean is already tiny, explicitly calculating and subtracting it over and over is just a waste of compute.

RMSNorm gambles on the assumption that the variance (the “signal” spread) will almost always dominate the mean (the “noise” shift).

RMSNorm completely drops the mean-centering step, simplifying the formula to:

\[RMSNorm(\vec{x}) = \vec{g} \odot \frac{\vec{x}}{\sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum x_i^2}}\]But wait. If we skip mean-centering, aren’t we destroying the elegant geometry we just built? How does this actually relate to standard LayerNorm?

To find out, I took the RMSNorm equation and mathematically forced the mean-centered transform ($x_i = x_i^{(1)} + \mu$) back into it. After expanding the squares and simplifying, the denominator perfectly resolves to $\sqrt{\sigma^2 + \mu^2}$ (for the full step-by-step mathematical derivation, see Appendix 4).

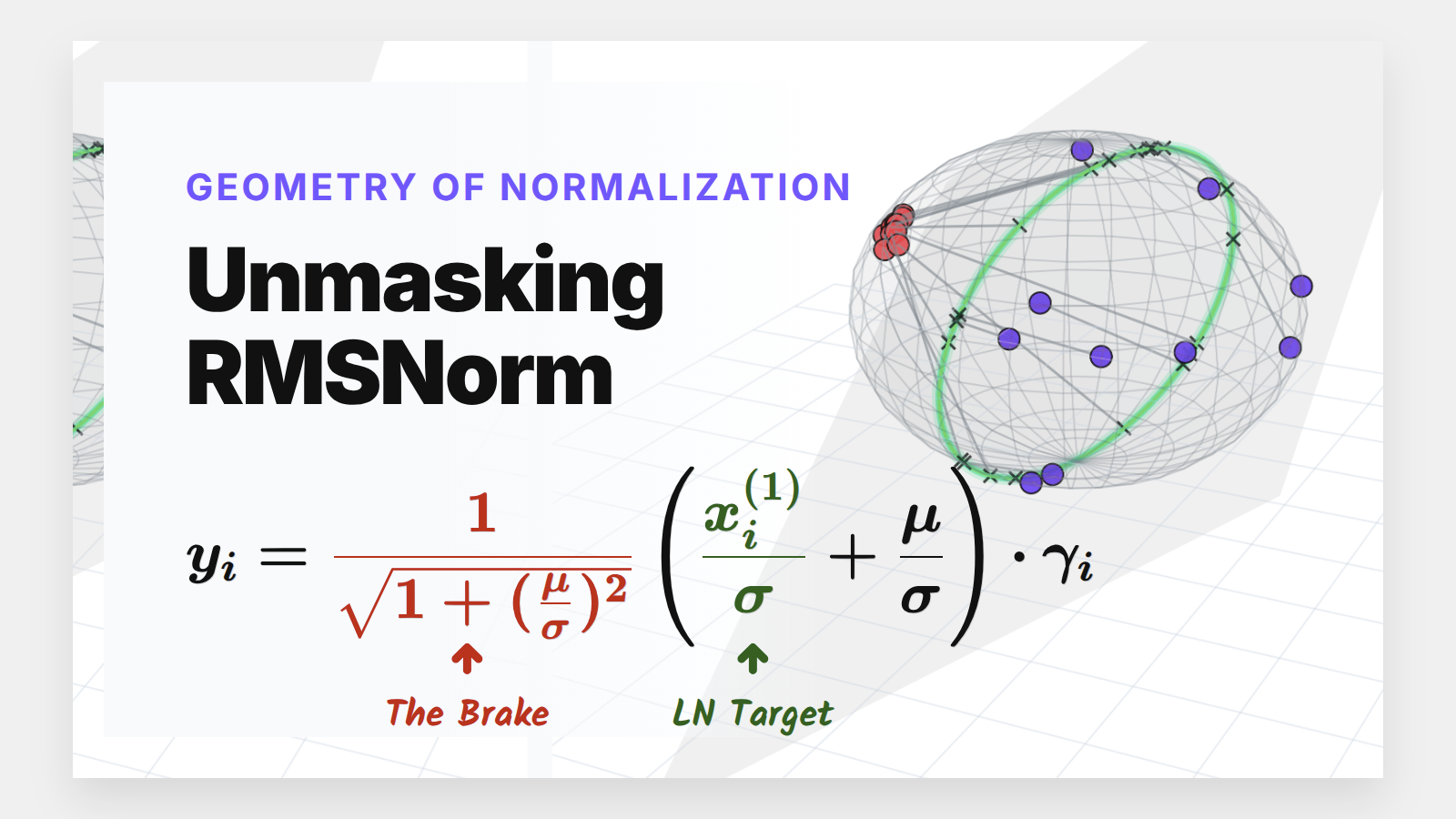

If we substitute this back into the full equation and separate the terms, we get a beautiful, unified formulation of RMSNorm:

\[y_i = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + (\frac{\mu}{\sigma})^2}} \left( \frac{x_i^{(1)}}{\sigma} + \frac{\mu}{\sigma} \right) * \gamma_i\]This equation is a goldmine. It proves that RMSNorm is mathematically identical to standard LayerNorm, just modulated by a dynamic “signal-to-noise” ratio ($\mu/\sigma$).

Let’s look at the three pieces:

The LayerNorm Core: $\frac{x_i^{(1)}}{\sigma}$ is exactly standard LayerNorm.

The Dynamic Bias: $\frac{\mu}{\sigma}$ acts as an automatic, data-dependent shift.

The Dampening Factor: $\frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + (\mu/\sigma)^2}}$ acts as an automatic brake.

This formulation dictates two distinct behavioral regimes for our models.

Case 1: The Healthy Network ($\sigma \gg |\mu|$)

In a well-behaved Transformer, the standard deviation of activations is naturally much larger than the mean.

If $\sigma$ dominates $\mu$, the ratio $\frac{\mu}{\sigma}$ approaches 0. Look at what happens to our equation: The dampening factor becomes $\frac{1}{\sqrt{1+0}} = 1$, and the dynamic bias vanishes.

RMSNorm closely approximates standard LayerNorm. It doesn’t land exactly on the perfect LayerNorm target equator because we completely skipped the explicit centering step. However, because the standard deviation is so large, the data is widely spread out and lands very close to that ideal $\sqrt{n}$ spherical ring, achieving a highly similar geometric goal while saving compute.

When $\sigma \gg \mu$, the raw data (blue dots) is naturally projected by RMSNorm to a spread-out ring that is very close to the exact LayerNorm target, without needing the explicit centering step.

When $\sigma \gg \mu$, the raw data (blue dots) is naturally projected by RMSNorm to a spread-out ring that is very close to the exact LayerNorm target, without needing the explicit centering step.

Case 2: The Unstable Network ($\mu \gg \sigma$)

What if the network spikes and the mean violently drifts away from zero?

In standard LayerNorm, the explicit mean subtraction would blindly correct this. RMSNorm doesn’t have that luxury. Instead, as $\mu$ grows, the ratio $(\mu/\sigma)^2$ explodes.

The dampening factor ($\frac{1}{\text{large number}}$) becomes tiny, forcefully shrinking the entire activation vector. Geometrically, instead of projecting to the equator of the hypersphere, RMSNorm tightly clusters the unstable, highly-shifted data at the “poles” of the sphere, suppressing its magnitude and punishing the network for the instability.

When $\mu \gg \sigma$, RMSNorm (crimson dots) doesn’t correct the shift. Instead, the dampening factor aggressively shrinks the vectors, clustering them tightly together away from the ideal LayerNorm target.

When $\mu \gg \sigma$, RMSNorm (crimson dots) doesn’t correct the shift. Instead, the dampening factor aggressively shrinks the vectors, clustering them tightly together away from the ideal LayerNorm target.

The Big Picture: RMSNorm vs LayerNorm

To really hammer this home, let’s look at a side-by-side comparison where both populations live together, similar to what we saw with the effect of epsilon.

RMSNorm is essentially performing a “lazy” LayerNorm. It works beautifully when the data behaves, but acts as a strict spatial regularizer when the data goes rogue.

A full comparison: High-variance data (blue) efficiently spreads out near the ideal LayerNorm equator, while low-variance, shifted data (crimson) is actively penalized and clustered near the poles.

A full comparison: High-variance data (blue) efficiently spreads out near the ideal LayerNorm equator, while low-variance, shifted data (crimson) is actively penalized and clustered near the poles.

Conclusion

By stripping away the algebra, we can see that normalization layers aren’t just statistical hacks; they are rigorous geometric constraints. They force chaotic, high-dimensional data to live on well-behaved, predictable manifolds (spheres and ellipsoids) so the subsequent attention layers can actually make sense of them.

RMSNorm’s success isn’t magic. It’s a calculated gamble that relies on the natural high-variance properties of deep neural networks to approximate the perfect spherical geometry of LayerNorm, while using a built-in dampening ratio to catch the model if it falls.

Code & Animations

The complete python script used to generate the 3D data, compute the projections, and render all the animations in this post is available in my repository.

Link to the project code.

Special thanks to Andy Arditi for his excellent research notes, and Paul M. Riechers for the formal geometric proofs.

If you have made it this far and found this article useful, you can buy me a coffee, it helps me keep writing posts like this one, as they’ve been taking more and more time :)) hopefully the quality shows off.

Appendix: Mathematical Derivations

Here are the step-by-step mathematical proofs for the geometric translations discussed in the main post.

1. Mean Centering as a Projection

We want to show that subtracting the mean is equivalent to subtracting the vector’s projection onto the unit vector of ones ($\hat{1}$). The standard formula for the mean is:

\[\mu_{\vec{x}} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i = \frac{1}{n}(\vec{x} \cdot \vec{1})\]We define the unit vector $\hat{1}$ by dividing the vector of ones by its length ($\sqrt{n}$):

\[\hat{1} = \frac{\vec{1}}{\sqrt{n}} \implies \vec{1} = \sqrt{n}\hat{1}\]Now, substitute this into a vector representing the mean shifted across all dimensions ($\mu_{\vec{x}}\vec{1}$):

\[\mu_{\vec{x}}\vec{1} = \frac{1}{n}(\vec{x} \cdot \sqrt{n}\hat{1})(\sqrt{n}\hat{1})\]Pulling the scalars out to the front gives:

\[\mu_{\vec{x}}\vec{1} = \frac{n}{n}(\vec{x} \cdot \hat{1})\hat{1} = (\vec{x} \cdot \hat{1})\hat{1}\]Thus, subtracting the mean is mathematically identical to subtracting the orthogonal projection onto $\hat{1}$:

\[\vec{x}^{(1)} = \vec{x} - \mu_{\vec{x}}\vec{1} = \vec{x} - (\vec{x} \cdot \hat{1})\hat{1}\]2. The Hypersphere Radius ($\sqrt{n}$)

We want to prove that dividing by the standard deviation scales a vector to a length of exactly $\sqrt{n}$. The variance of our mean-centered vector is the average of its squared components:

\[\sigma_{\vec{x}}^2 = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n (x_i^{(1)})^2 = \frac{1}{n} ||\vec{x}^{(1)}||^2\]Taking the square root gives us the standard deviation:

\[\sigma_{\vec{x}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} ||\vec{x}^{(1)}||\]When we perform the normalization step ($\vec{x}^{(2)} = \frac{\vec{x}^{(1)}}{\sigma_{\vec{x}}}$), we substitute the definition of $\sigma_{\vec{x}}$:

\[\vec{x}^{(2)} = \frac{\vec{x}^{(1)}}{\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} ||\vec{x}^{(1)}||} = \sqrt{n} \frac{\vec{x}^{(1)}}{||\vec{x}^{(1)}||}\]3. The Effect of $\epsilon$ on Vector Length

We want to see how adding $\epsilon$ alters the final length of our normalized vector. We start with the normalization equation including $\epsilon$:

\[\vec{x}^{(2)} = \frac{\vec{x}^{(1)}}{\sqrt{\sigma_{\vec{x}}^2 + \epsilon}}\]Let’s find the magnitude (norm) of this new vector:

\[||\vec{x}^{(2)}|| = \frac{||\vec{x}^{(1)}||}{\sqrt{\sigma_{\vec{x}}^2 + \epsilon}}\]Substitute our definition of variance ($\sigma_{\vec{x}}^2 = \frac{1}{n}\lVert\vec{x}^{(1)}\rVert^2$) into the denominator:

\[||\vec{x}^{(2)}|| = \frac{||\vec{x}^{(1)}||}{\sqrt{\frac{1}{n}||\vec{x}^{(1)}||^2 + \epsilon}}\]To simplify, factor $\frac{1}{n}$ out from the terms inside the square root:

\[\sqrt{\frac{1}{n} (||\vec{x}^{(1)}||^2 + n\epsilon)} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} \sqrt{||\vec{x}^{(1)}||^2 + n\epsilon}\]Substitute this back into the denominator, bringing the $\sqrt{n}$ up to the numerator:

\[||\vec{x}^{(2)}|| = \sqrt{n} \left( \frac{||\vec{x}^{(1)}||}{\sqrt{||\vec{x}^{(1)}||^2 + n\epsilon}} \right)\]4. Full RMSNorm Derivation

We want to show how RMSNorm mathematically simplifies when we explicitly expose the mean and variance. We start with the standard RMSNorm definition:

\[y_i = \frac{x_i}{RMS(\vec{x})} * \gamma_i \quad \text{where} \quad RMS(\vec{x}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=1}^n x_j^2}\]We introduce the transformation to separate the mean-centered input from the mean: $x_j = x_j^{(1)} + \mu$. Because it’s mean-centered, the sum of the mean-centered inputs is zero ($\sum_{j=1}^n x_j^{(1)} = 0$). We also know that the variance $\sigma^2$ is the mean of the squared mean-centered inputs ($\sigma^2 = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=1}^n (x_j^{(1)})^2$).

Step 1: Expand the squared term Replace the raw input $x_j$ with the transformed version inside the square root and expand using the binomial theorem:

\[RMS(\vec{x}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=1}^n \left( (x_j^{(1)})^2 + 2x_j^{(1)}\mu + \mu^2 \right)}\]Step 2: Distribute the summation Split the equation into three separate sums:

\[RMS(\vec{x}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=1}^n (x_j^{(1)})^2 + \frac{2\mu}{n}\sum_{j=1}^n x_j^{(1)} + \frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=1}^n \mu^2}\]Step 3: Simplify the sums The middle term contains $\sum_{j=1}^n x_j^{(1)}$, which is 0. The entire middle term vanishes. The last term sums the constant $\mu^2$ exactly $n$ times, resulting in $n\mu^2$. Dividing by $n$ leaves just $\mu^2$:

\[RMS(\vec{x}) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=1}^n (x_j^{(1)})^2 + \mu^2}\]Step 4: Substitute the variance and factor Recognizing the remaining summation is exactly the definition of variance ($\sigma^2$), we get:

\[RMS(\vec{x}) = \sqrt{\sigma^2 + \mu^2}\]To isolate the ratio of the mean to the standard deviation, we factor $\sigma^2$ out of the terms inside the square root:

\[RMS(\vec{x}) = \sqrt{\sigma^2 \left( 1 + \frac{\mu^2}{\sigma^2} \right)} = \sigma\sqrt{1 + \left(\frac{\mu}{\sigma}\right)^2}\]Step 5: Substitute back into the full equation Now, return to the original RMSNorm equation ($y_i$). Substitute the transformed input ($x_i^{(1)} + \mu$) into the numerator, and our newly derived expression into the denominator:

\[y_i = \frac{x_i^{(1)} + \mu}{\sigma\sqrt{1 + (\frac{\mu}{\sigma})^2}} * \gamma_i\]Step 6: Split the terms to reach the final form Factor out the square root portion, and separate the numerator over the standard deviation ($\sigma$) to explicitly show the LayerNorm component and the dynamic bias component:

\[y_i = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 + (\frac{\mu}{\sigma})^2}} \left( \frac{x_i^{(1)}}{\sigma} + \frac{\mu}{\sigma} \right) * \gamma_i\]